A Brief Human History of Devil's Lake State Park

Over 3 million people visit Devil’s Lake State Park each year, making the Park one of the most cherished parcels of public land in the United States. But who occupied this land before it was a Park? And how did the Park come to be in the first place? We offer a brief overview of an area many people have loved and revered for tens of thousands of years.

Ho-Chungra People Have Always Been Here

People have inhabited the lands surrounding Devil’s Lake for tens of thousands of years. Archeologists have discovered evidence of human activity as far back as 15,000 years ago, when the most recent Ice Age receded. However, Ho-Chunk oral tradition goes much further, suggesting Ho-Chungra people, whose lands range throughout the Great Lakes states, may have lived here through the last three ice ages (over 350,000 ago). As the Ho-Chunk say, they “have always been here,” living in reciprocity with the land and developing a rich culture.

The Wisconsin Glacier Left a New Lake Behind

When the Wisconsin Glacier receded approximately 15,000 years ago, it left a new lake behind. The lake was created when the Wisconsin Glacier impounded an ancient river valley (which may have been the ancestral Wisconsin River or Baraboo River), blocking it above and below the large gap the river had cut into the southern ridge of the Baraboo Range.

In post-glacial years, native peoples visited Devil’s Lake regularly, though there is no evidence of a long-term settlement there. While Ho-Chunk peoples (formerly known as Winnebago) visited the tribe most regularly and had the largest influence on the land and local culture, other tribes including the Sauk, Fox, and Kickapoo also passed through the area.

What Do Native People Call the Lake?

The Ho-Chunk call the lake “Tewakącąk,'“ which translates to Sacred Lake. Another tribe called it Minnewaukan, or Spirit Lake. White historians have debated what native people called Devil’s Lake before European settlers arrived, perhaps because there were few written records and a variety of peoples had relationships with the area. None of the tribes had negative associations with the Lake, despite numerous accounts that some tribes the place was haunted by evil spirits.

Europeans Visit Sacred Lake and Permanent Development Begins

The first European settler of record to visit Devil’s Lake was John De La Ronde, who likely found it by paddling up the Baraboo River to Baraboo, then heard of the nearby lake from local Ho-Chunk natives. Increase Lapham, the well-known UW scientist and naturalist, visited and circumnavigated Devil’s Lake in 1849, no mean task given the boulder fields that extended to the shoreline on three of the fours sides and the jungle of down trees and thick brush that likely protected the shoreline. As you might expect, after a handful of white settlers found Devil’s Lake, word quickly spread about the cool place they had “discovered.”

After the initial discovery of Devils Lake by Europeans, development quickly followed. The 1850s saw the first building, a bathhouse, erected on the Lake’s shoreline, and increased attention in the media, including a Milwaukee Journal article highlighting the area. Local folks from the Baraboo, Wisconsin Dells and Madison areas had already made Devil’s Lake a regular pleasure spot, visiting in fair weather for picnics, swimming, and exploring. In 1854, Noble C. Kirk purchased property on the South Shore and created Kirkland, which eventually became a rustic resort open to the public. Over the years, Kirk cleared large areas of his property to install cottages, orchards, and picnic grounds to accommodate and entertain the growing crowds railroad service would bring.

The Arrival of the Railroad and Tourist Culture

After years of encouragement by the state legislature and business interests, the Chicago & North West (C&NW) Railroad finally completed a line along Devil’s Lake’s east shoreline in 1873. With the rail line in place, the flood gates opened on Devil’s Lake. Visitors from Milwaukee and Chicago began visiting in crowds, bringing with them demand for shelter, services, and recreation.

While Kirkland developed, other hotels sprung up to accommodate visitors. The Minniwauken House (1866) was the grandest affair, built on the Lake’s north shore and able to initially accommodate 20 guests. The Minniwauken House was eventually expanded and renamed the Cliff House; in 1884 The Annex was added to the property, making room for up to 400 people. The Cliff House was the only accommodation in the history of the North Shore, but the South Shore saw further development over time, including the Lake View Hotel and the Messenger Hotel and Resort, located on the southeast and southwest shores, respectively.

The Cliff House hotel.

The Cliff House Hotel, 1898.

Naming the Lake

Historical records show the name “Devil’s Lake,” along with other names, was still being debated as late as 1871. The earliest European name seems to have been “Lake of the Hills,” but other suggestions included “Wild Beauty Lake” (Kilbourn Mirror) and “Junita Lake” (Milwaukee Journal). In 1858, the Baraboo Republic officially opined “Spirit Lake” was best, but all these names fell to the sexy and illustrious “Devil’s Lake.” While some have linked “Devil’s Lake” to a misinterpretation or purposeful bending of the native name “Sacred Lake,” it is just as likely that is was simply a catchy name popular at the time for ANY interesting lake or landmark. There are at least seven “Devil’s” lakes in Wisconsin, and scores more landmarks throughout the country named similarly.

Devils Lake Becomes a Wisconsin State Park

The early 20th century brought a groundswell of national concern for the conservation and preservation of valuable scenic and natural resources, and Wisconsin citizens joined the movement to identify and create protected parks for public benefit.

In 1906, Baraboo locals formed a committee to study tourist impacts on the area and the potential for a state park. Later that year, they published a 38-page pamphlet, “An Appeal for the Preservation of the Devil’s Lake Region,” which they sold for 50 cents. Written in lofty prose and appealing to a high sense of public and moral good, the pamphlet identifies the primary assets of the Devil’s Lake area, specifically explaining the geologic, forest, archaeologic, botanical, and avian highlights of the proposed park. The committee specifically aimed to remove hotels and timber and mining resource extraction from the area, as well as protect all the drainages leading to Devil’s Lake. The Milwaukee Journal later endorsed the Appeal in an editorial, following with a lengthy story on the issue later in 1906. The state legislature put the proposal to a vote in 1907, but the bill failed by one vote.

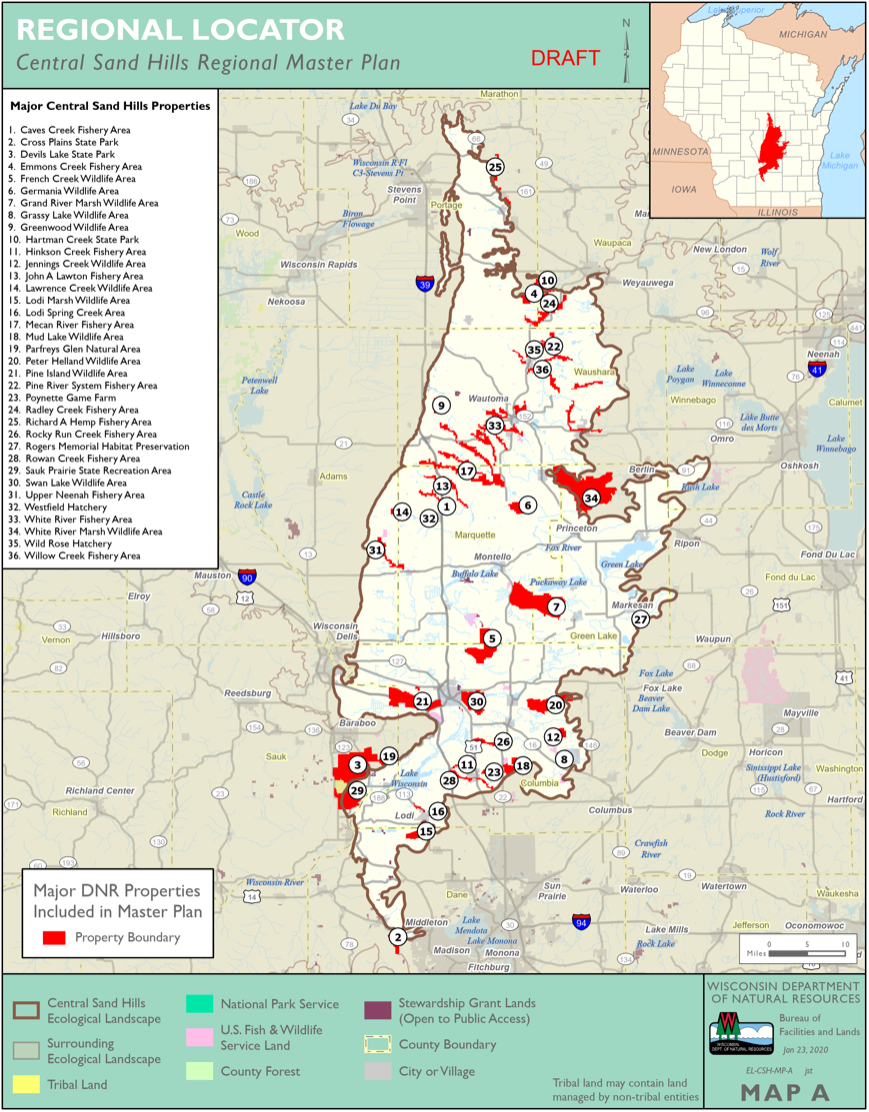

Proposed map of Devil’s Lake State Park from the 1906 publication, “An Appeal for the Preservation of the Devil’s Lake Area.”

Momentum was strong toward park-building, however, and the push to create a park at Devil’s Lake continued. In 1909, the state commissioned Boston landscape architect John Nolen to identify Wisconsin natural resources with the most park potential, and Devil’s Lake made Nolen’s “top five” list, along with Wisconsin Dells, Door County’s Fish Creek area, and the Wyalusing area near Prairie du Chien.

The State Park board began buying property around Devil’s Lake in 1909 and by 1910 had acquired 740 of the 1150 acres it needed for the park. These properties included the Cliff House, Kirkland, Lake View, and Messenger hotel properties, as well as numerous smaller cottage properties in the area. While some property owners resisted the park movement and refused to sell their property, many cottage owners cooperated, selling their land to the State for $1 in exchange for a 60-year rent and tax-free lease on their properties. The state also promised to build a proper road into the area and stop the quarrying that had been going on since 1906.

Postcard showing pier, tourist boat and waterslide at North Shore of Devil’s Lake. Date unknown.

By 1911, the state controlled 1100 acres in the proposed park, making it easier to convince legislators to pass the bill creating Devil’s Lake State Park, Wisconsin’s third state park. The first superintendent lived for a short time at the Messenger Hotel.

In 1919, the legislature authorized the Conservation Commission to buy the 110 acre parcel owned by the American Refractories Company to stop the blasting and quarrying on the East Bluff. The company moved a couple miles down the South Shore road and set shop up there, as it was then outside the Park boundary. In 1967, the Park expanded its eastern boundaries and quarrying ended in the area. The area the quarrying operation last operated, known by local climbers as the New Sandstone area, remains closed to recreational rock climbing.

The CCC Years

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, the federal government initiated the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as one of many programs intended to revive the economy, create jobs, and improve the infrastructure on public lands. Fortunately for us, Devils Lake State Park became a CCC project and hosted a camp of 200 "CCC boys" from 1933 to 1942. The camp was located at the present-day CCC Parking lot and Group Campground.

The CCC boys worked on a variety of building and trail construction projects in exchange for a small wage plus room and board. Whenever you see a beautiful stone building with ample character in the Park, you can bet it was CCC handiwork. Well-known examples include the Chateau on the North Beach, the Park Headquarters near the North Shore entrance station, and the beachside pavilion just north of the Chateau. Other buildings include the park staff building along the railroad tracks and the bathhouse in the Northern Lights campground. All the steep trails up the bluffs, including the Potholes Trail, Balanced Rock Trail, West Bluff, East Bluff and the epynomonous CCC Trail owe their quartzite steps to the CCC crew.

The Devil’s Lake Concession Company

In 1949, local Baraboo business people founded the Devil’s Lake Concession Company, a non-profit organization who shares its profits with the Park. The DLCC has since run both the North Shore and South Shore food and rental concessions, offering groceries, meals, and boat rentals to campers and visitors. The DLCC has raised over $2 million for Devil’s Lake State Park, contributing needed funds when the Park cannot runs into budget constraints for equipment, wages, or special projects. For example, the DLCC donated $164,583 toward remodeling the Chateau in 2012.

Natural HistorY interpretation at Devil’s Lake

Ken Lange was not only the first full-time Naturalist at Devil’s Lake State Park, but also the first naturalist hired by the Wisconsin State Park system. Ken led interpretive walks and talks, assisted visiting scientists in Park research efforts, developed the Park’s Nature Center, and carried the torch for conservation and protection. He wrote a number of important natural and human history books, including Ancient Rocks and Vanished Glaciers: A Natural History of Devil’s Lake State Park, A Naturalists’s Journey and Song of Place. After 30 years of public service at Devil’s Lake, Ken retired in 1996.

Sue Johansen-Myoleth is current Park Naturalist and has been with the Park since 2010. You can find upcoming nature walks and talks with Sue and her seasonal staff on the Devil’s Lake State Park calendar.

Park Stewardship

The Wisconsin DNR adopted Devil’s Lake’s current Master Plan in 1982. The Department began a new master planning process for Devil’s Lake in 2020, which is part of a larger master plan for the Central Sand Hills Ecological Landscape. To receive updates on the Master Planning process, subscribe here.

The Friends of Devil’s Lake, a non-profit group, organized in 1997. Like many Friends groups of Wisconsin State Parks, the Friends core purpose is to facilitate financial donations to Devil’s Lake State Park, which may not accept donations directly from private citizens. The Friends organize and facilitate a number of volunteer-based programs to support, improve and enhance visitors’ experience at Devil’s Lake.

Steve Schmelzer started as a Park ranger in 1992, and became Devils Lake State Park superintendent in 2010. Schmelzer left as Superintendent in 2019 for a position managing all the Wisconsin State Parks in the Southwest region, then soon was promoted to Wisconsin State Parks Director. Jim Carter was appointed as interim Park Superintendent in 2019, and took the job full-time 2020.